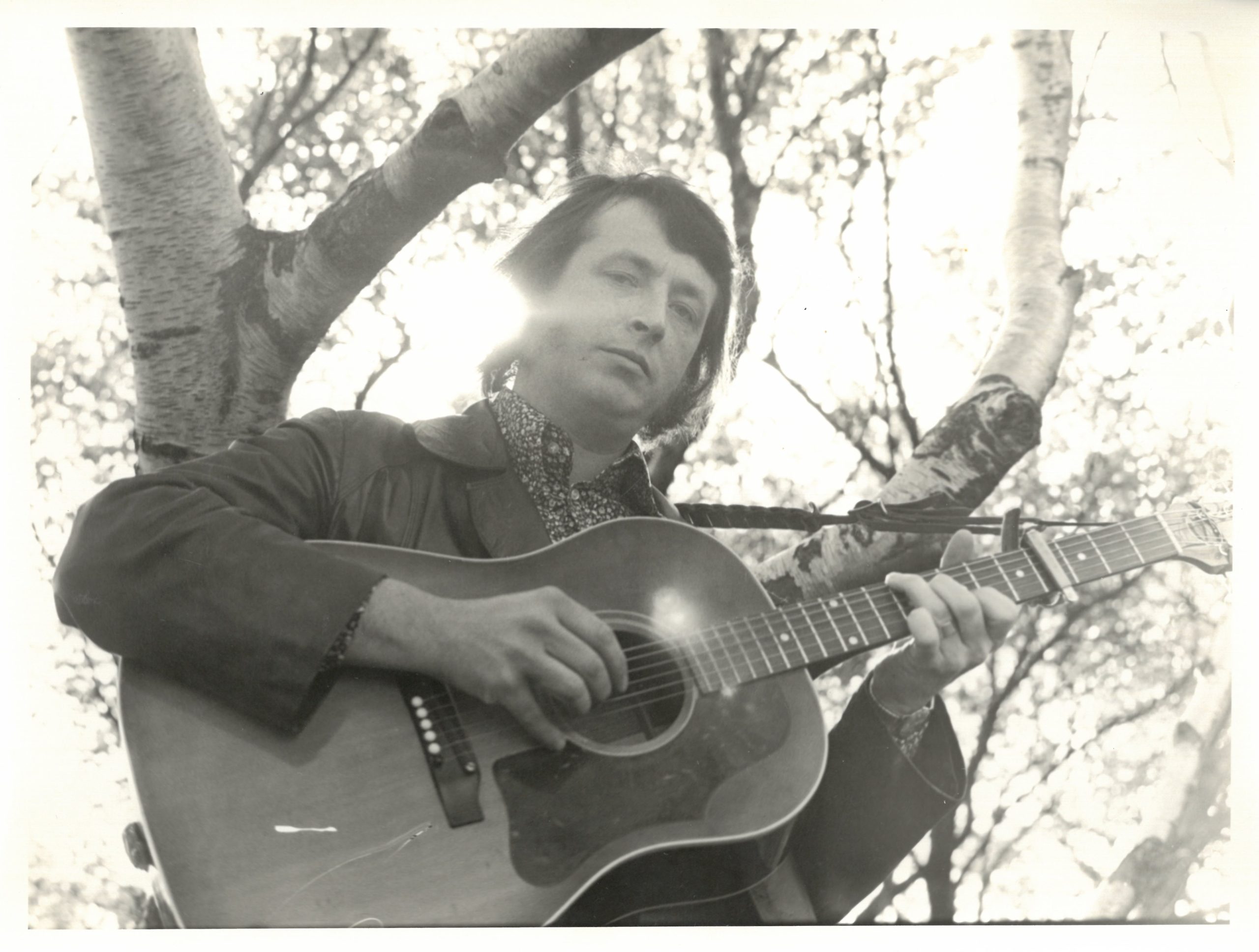

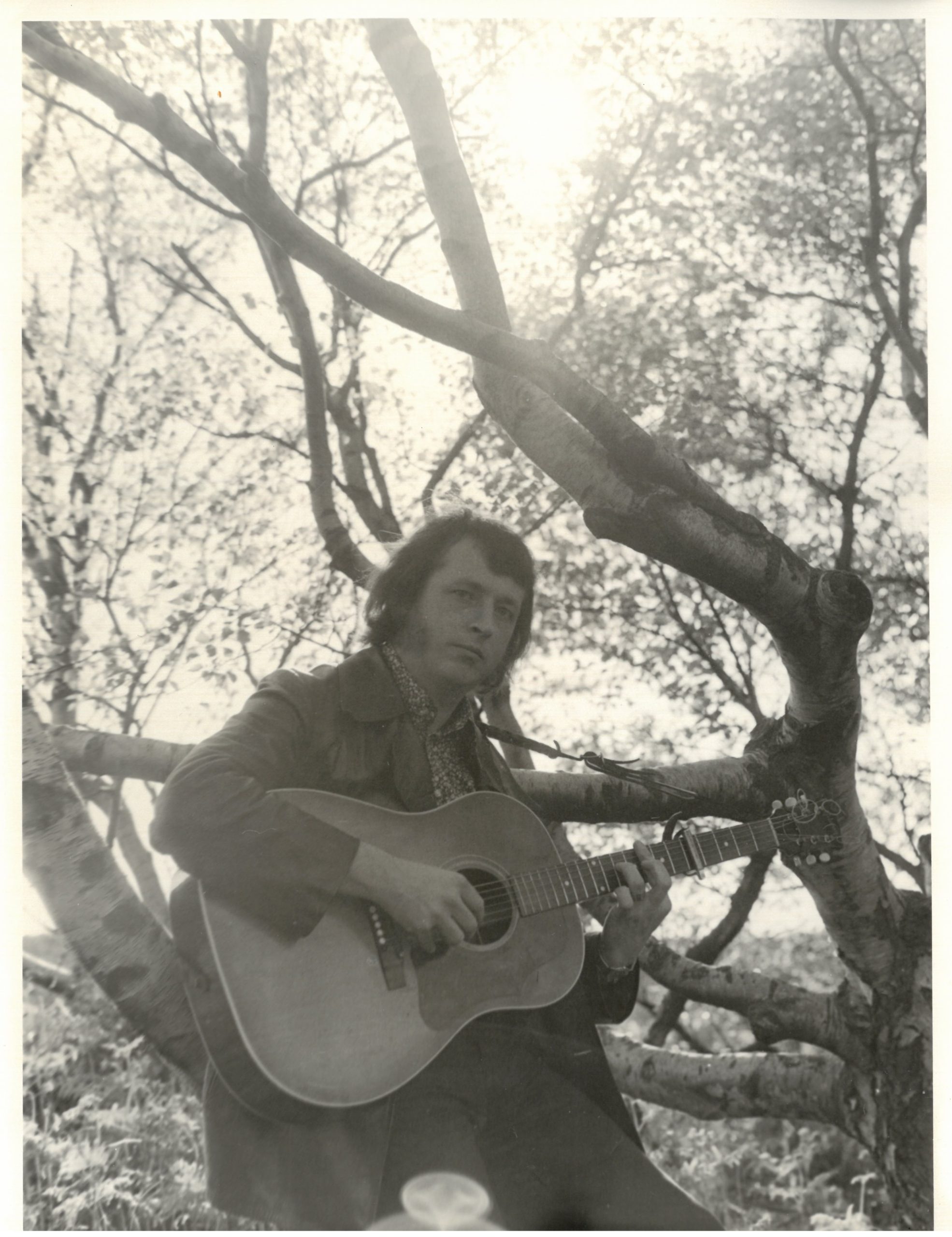

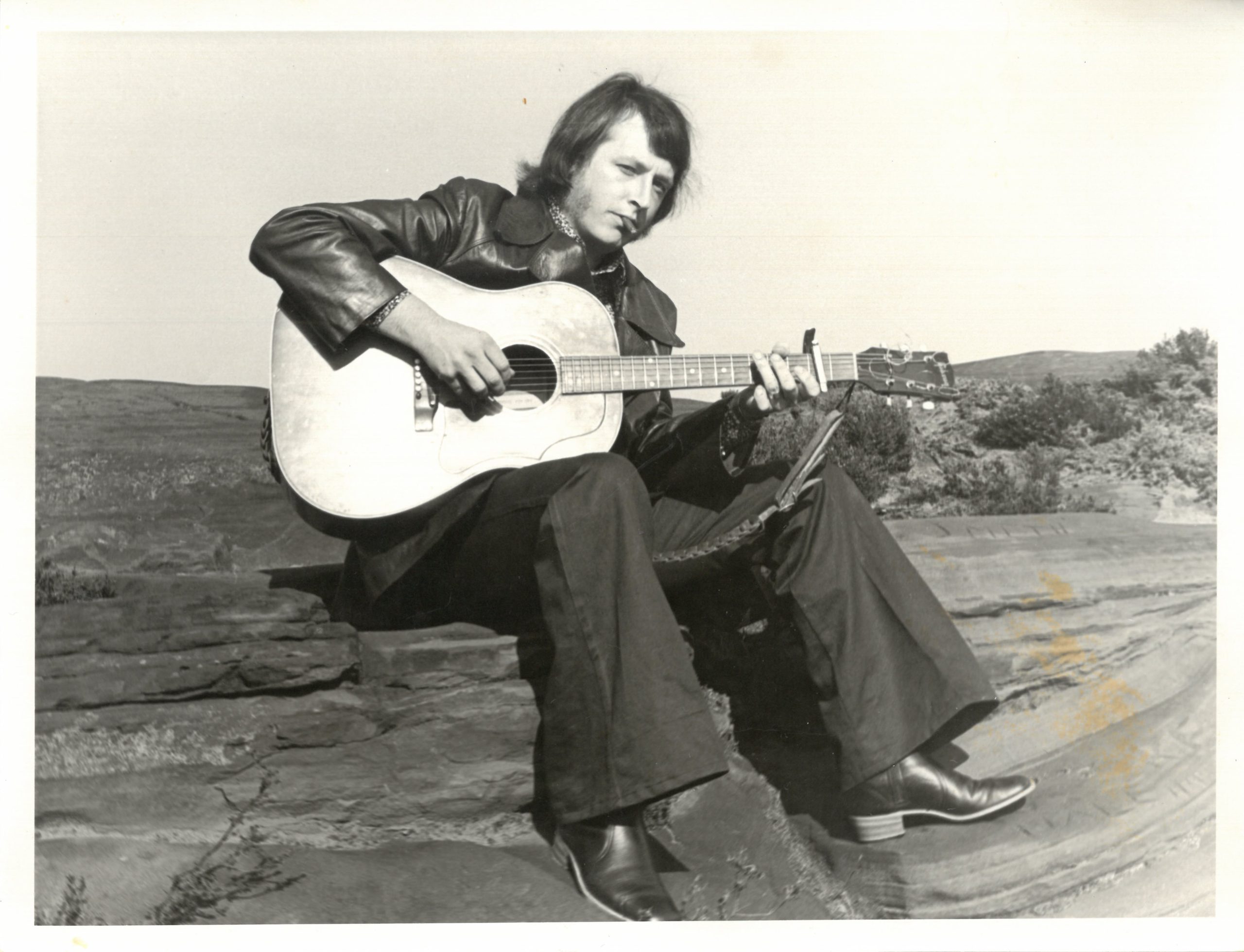

Pete Young

Pete Young

A Tribute To His Dad

The story of Pete Young, by his son – Richard Young

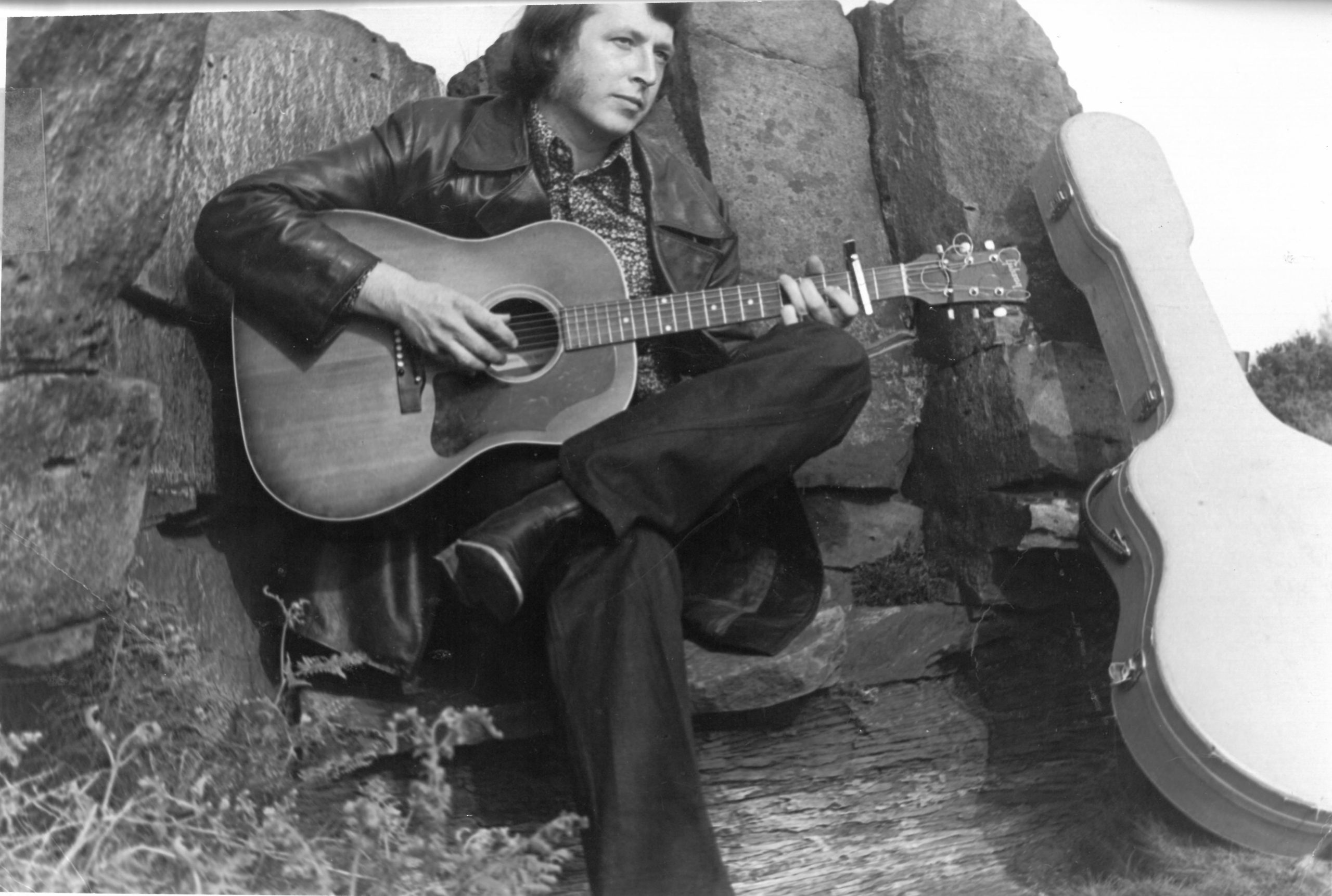

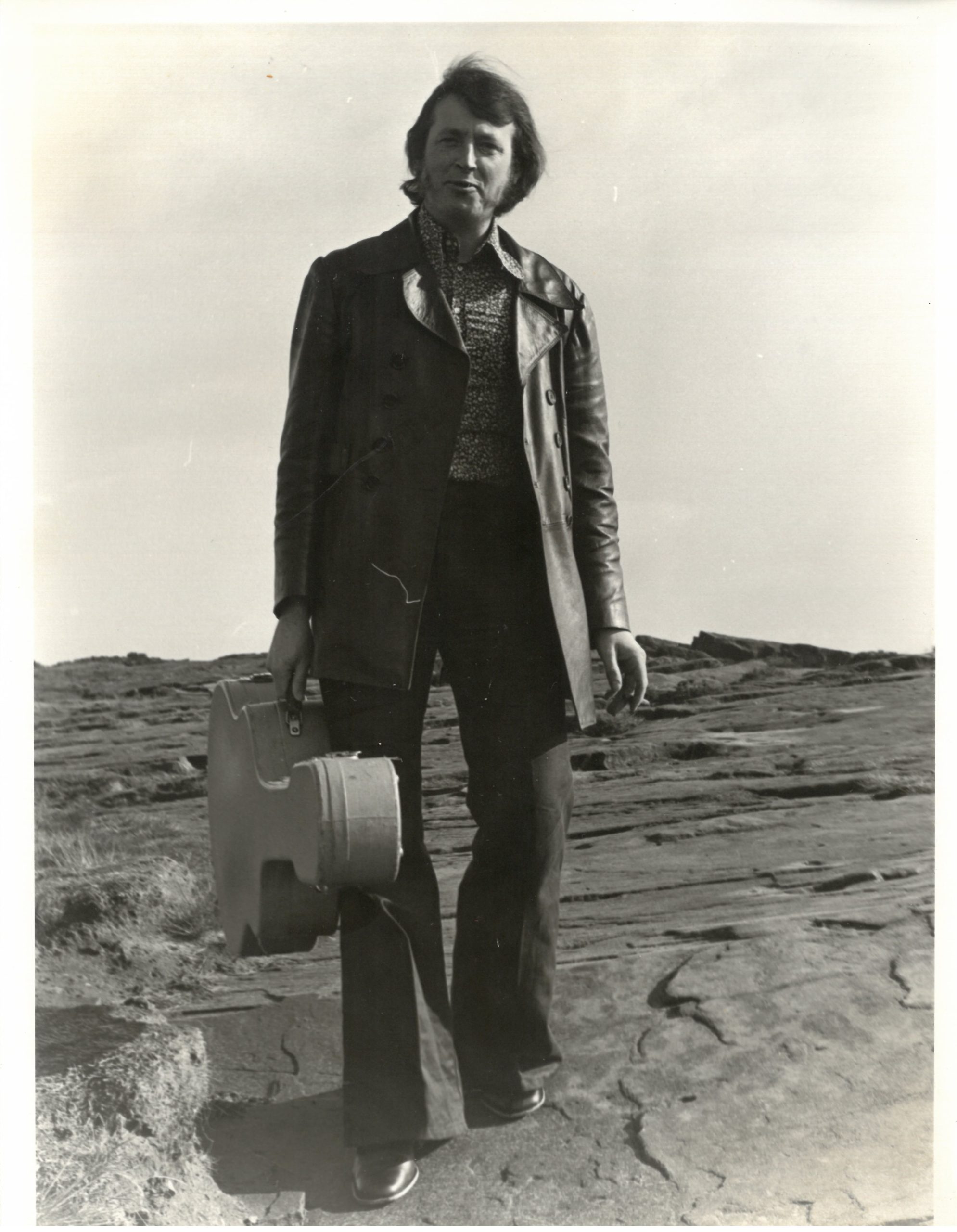

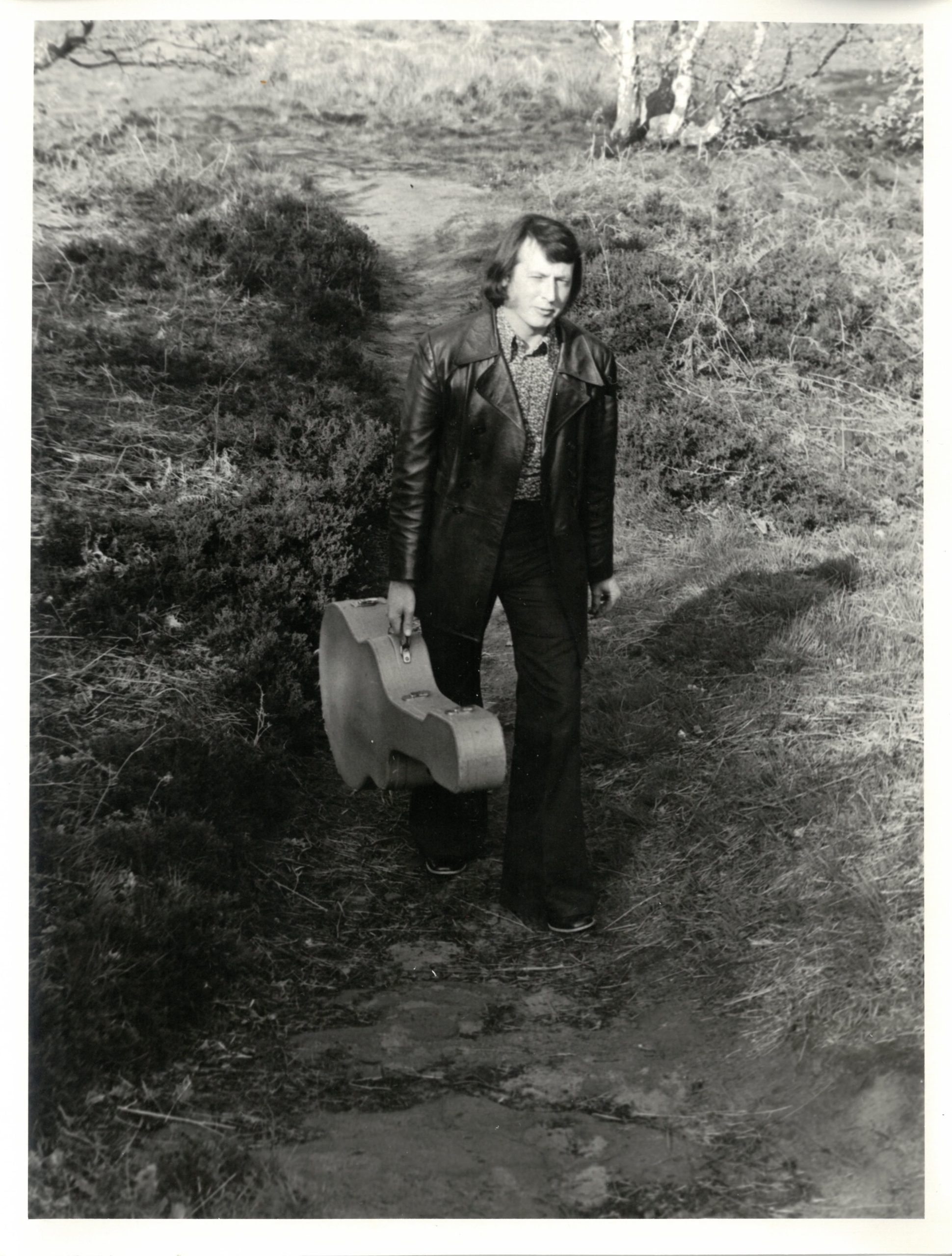

Pete Young never drove a Volvo; he never visited Uganda; he absolutely detested M.F.I; he never even had a pint on the Lower Side of Upper Middle Class and, to my knowledge, never lived on Cherry Tree Avenue. Stroo! And yet, all these were staples of his setlist in the folk clubs of Wirral, Cheshire and beyond in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

A Tribute To His Dad

The story of Pete Young, by his son – Richard Young

Pete Young never drove a Volvo; he never visited Uganda; he absolutely detested M.F.I; he never even had a pint on the Lower Side of Upper Middle Class and, to my knowledge, never lived on Cherry Tree Avenue. Stroo! And yet, all these were staples of his setlist in the folk clubs of Wirral, Cheshire and beyond in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

You may even have joined in a chorus or two, he certainly would have asked you to! In his later years he desperately wanted to get involved with this project, but illness and the sands of time have meant that it is me, his son, trying to encapsulate his story, from a self-taught beginner in Havant and Waterlooville, to, using his own words, a ‘microstar’.

I am unsure precisely how his love affair with folk music, the blues and traditional jazz started but I do know that, in his mid-teens, his world changed. In March 1960, aged 15, Pete took the bus from Havant and Waterlooville to Portsmouth and attended a gig in what might be described as ‘downbeat jazz club’. Here he watched a man that would become a huge inspiration to him, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. Pete received two lessons that night. Firstly, a musical one. I can imagine him watching Ramblin’ Jack’s famed flat and fingerpicking styles, wide-eyed, ears pricked, taking mental notes to develop his own signature flatpicking style, whilst taking in the ‘ramblin’ that Jack was also famous for.

Inspired no doubt, by the ramblin’ of Jack, the clear socialism of Broadside and the writings of Dylan and others, anti-war songs and social commentaries can be found across Pete’s writings, particularly in the early days. For instance, ‘The Trooper’, written in August 1964, when he was 19. A tale of a soldier going off to fight in Germany, his family being proud of the medals he keeps sending back – ‘they were of silver, bronze and gold’ – until the soldier himself fails to return and the medals become tarnished with ‘tears a-flowing o’er them’. If you are familiar with Pete’s later writings, something so serious and hard-hitting may seem hard to place, but he kept a folder of such songs, type-written, and by now worn and battered with yellowing pages. August 1964 seems to have been a month of anti-war songs, with ‘The Ballad of Two Heroes’ being written just three days after ‘The Trooper’. This one focusing on the horrors of the First World War from the perspective of a ‘valiant English lad’ and a ‘young German boy’. When you compare the contents of Broadside in 1964 and the folder of songs written by Pete, the correlation between the two is clear. Over in the US concerns were rife with Vietnam, Civil Rights and the struggle between war and peace, whilst similar concerns are found in Pete’s lyrics. Then things began to change. In the UK, Bob Dylan’s popularity was surging and he had performed in Liverpool’s Odeon Theatre in May 1965, a gig that Pete attended. As Dylan’s fame grew Pete worried about people thinking he was merely jumping on Dylan’s coat tails and hitching a ride. He changed tact, merging his quick wit, ‘joak’ writing and musical ability to produce a blend of satire, outright comedy, social justice and the odd X-rated comment (OK, so maybe there’s more than the ‘odd one’!). A truly unique booking at the time for many a folk club.

His second lesson, one in life’s vices. Upon arriving home Pete’s mum, Edna, was not happy, giving him a stern glare Pete wondered if the three pints of bitter might be showing on his fresh teenage face but, giving a short shrift, she said ‘have you been smoking?’. The relief on his face must have been a picture, his mum was not concerned about the underage alcohol consumption, nor even the dark and downbeat jazz club, just as long as he hadn’t had a cigarette. His dad, Len, also a keen guitarist, simply asked what Ramblin’ Jack was like. A love affair had begun. From this point on, Pete was an avid subscriber to several American folk pamphlets, including Broadside. Pete claimed that it was through one of these pamphlets that he read and learnt, a certain ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ by Dylan. He often claimed that was one of the very first people to play that particular song in the UK, due to small UK circulation numbers of the magazine. This claim is impossible to verify but I don’t think it would be too far off the mark. Regardless of the accuracy, Pete began a journey into a world of flatpicking, fret boards, harmonicas, and many more smoke-filled, downbeat rooms.

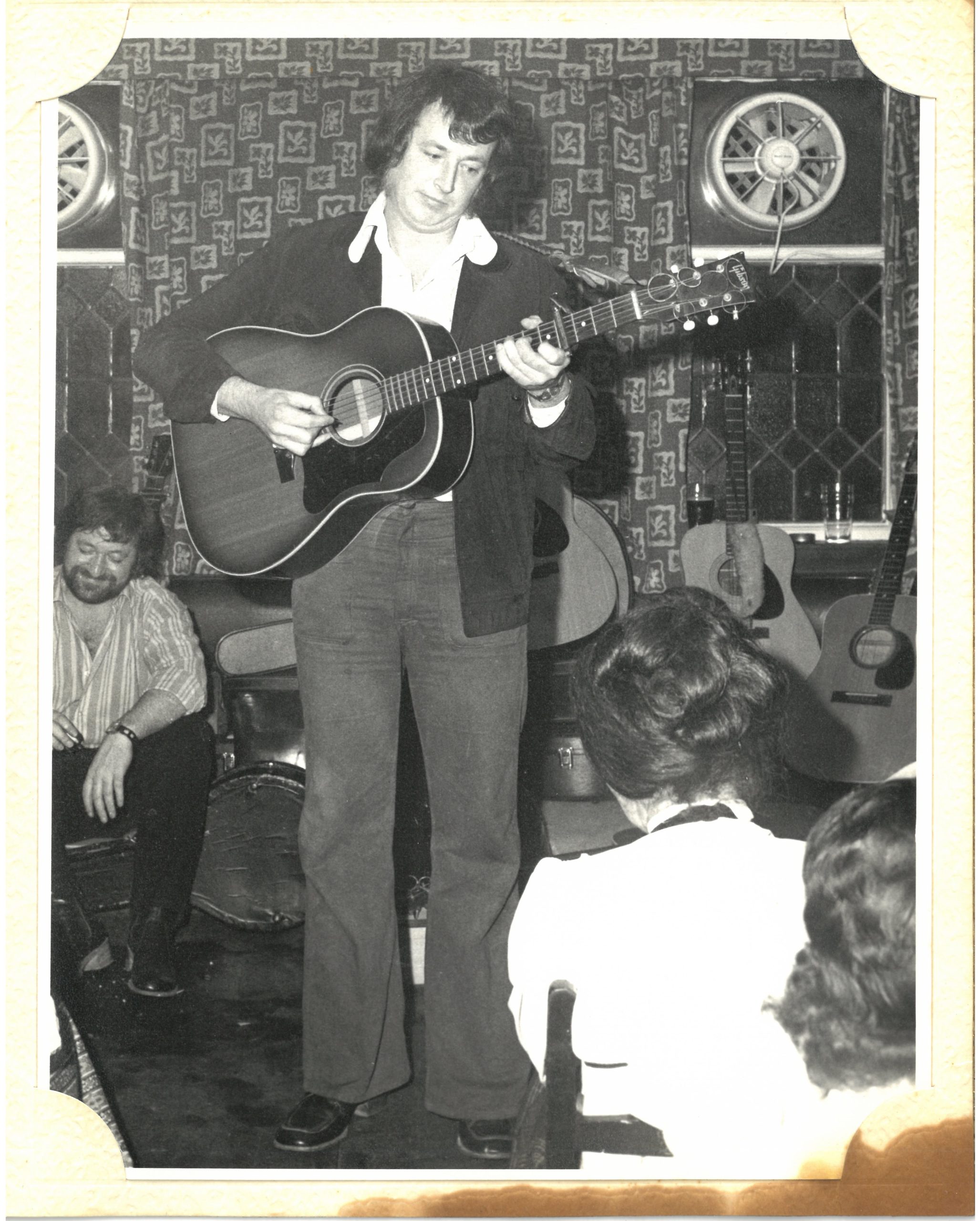

Local folk clubs became a huge part of Pete’s life. He found enjoyment there through the people he met, not just the music. Obviously, he enjoyed the singing and hip-swinging on stage but he found equal enjoyment at the bar, or in the doorway having conversations with many folks as they came and went. In 1978 he attended Parkgate Folk Club, not for the first time, but this time would be significant. As he always did, Pete bought a strip of raffle tickets from Georgina. What was significant about this was who he did not buy a raffle ticket from, my mum, Chris. She also sold tickets but was so smitten with Pete that she was far too shy to approach him and sell him a ticket. Eventually she must have done something or this article wouldn’t be getting written but she won’t tell me what! I’m sure Pete knew that he had an admirer and would’ve absolutely played up to it. His performance that night might have had a few more hip sways and thrusts than normal.

Attendances, and probably performances, at folk clubs in Mollington, or the Magazine in New Brighton, on a Sunday, the Black Horse on a Tuesday and Parkgate on a Wednesday were front and centre of Pete’s social calendar. He enjoyed watching and listening to many performers, including Harvey Andrews and Jack Owen. Through the folk scene he met numerous others who became friends such as Pete McGovern and Brian Jacques. I know he how much he loved The Tom Topping Band, and how much he held the friendships with the trio close to his heart. One of my own fondest memories as a child was asking him to put a certain cassette on during Sunday dinner, it was Colin Henderson’s ‘All in a Days Work’. I think my dad got quite a buzz that he was able to say these were his mates, and his son was asking for their music, and not whatever was on the radio, or in the charts. The people, the stories and the camaraderie were what I think touched Pete the most. Gigs followed far and wide. He was offered gigs across Merseyside and Cheshire, as well as in the Birmingham area. The latter came through his contacts with Jasper Carrott, who booked him for one particular gig that Pete thought had gone very wrong. I do not know the venue, but Pete performed with his usual gusto, and tried to encourage a raucous engagement from the audience. Pete told me that he was met with utter confusion and bewilderment. When the gig was over, stood at the bar, pint of bitter and smoking a Hamlet, a gentleman came over, and in his dull Black Country tomes just said ‘That was the best night of my loife’, completely aghast my dad just thought ‘well you could’ve bloody shown it!’. I am not sure what his actual reply was, but it would not have been far off that!

Though Pete travelled the length and breadth of the Wirral, Liverpool and Cheshire performing, and venturing occasionally to the Midlands, he would travel all over to be entertained. One tale he would tell with glee was when he went to the Cambridge Folk Festival. He drove down with a friend from the local circuit, John Land. John was visually impaired, and would often use this to his benefit. Seeing the queue for the bar, Pete informed John that there would be a bit of a wait. John simply said, ‘Youngie, where’s the bar?’ and then ‘watch this’, as he walked, white stick in hand clearing his own path, Pete following behind. They were served within minutes, much to Pete’s delight. John thought it bizarre, and couldn’t understand why people did not think he should queue like everyone else, ‘bloody idiots’ was his phrase.

Whereas some people may decline a gig or an appearance due to work commitments, Pete would decline shifts, overtime, or even knock off early, to ensure he could be there. Fellow workers at Bemrose Printers in Aintree, Liverpool, would complain that Pete wasn’t doing the usual 3-11 shift, but instead finishing at 9.30. His bosses and managers allowed it as he’d worked at such speed, with such accuracy in the re-touching department, that he had already done a shift’s worth of work and could quite happily get to Parkgate to find a corner for a pint and a natter. Pete was also willing to help out acts in the local area if he could. At some point a couple came over from the United States to perform. Someone close to the top brass at The Black Horse informs that their names were possibly Sandy and Jackie, though no-one is quite sure. Though the specifics of this are lost to time, Pete put them up for at least one night in the late 1970s, or early 1980s. When the couple arrived at Pete’s house in Eastham, Wirral, Jackie went straight to the fridge, with the usual manners of an American ‘over here’, opened it with haste and exclaimed ‘He’s got bacon, proper ******* bacon’ whilst Sandy was more understated and commented about the jokes, the humour and the wide vocabulary Pete used during the gig at The Black Horse, suggesting ‘no wonder he’s a fantastic wordsmith, look at all these books!’.

Another part of Pete’s life was his writing. He never went anywhere without a notebook and pen. He had been known, in his later years, to get off the Number 42 bus in Bromborough Village, en route to the Royal Oak or The Bromborough pub for a pint, and need to pop into the Post Office to buy a pen. He had forgotten his, left it by the telephone in all probability, but he never knew when a song would appear, a joke could be written or a puzzle completed. Since his passing I have obtained folders, and folders, of handwritten notes, essays, songs, poems and even a novel. In the 1970s and 1980s he began to write for television. He wrote scripts for sit-coms, jokes for television presenters, and contributed towards shows such as ‘Two of a Kind’ and Comic Relief. He kept everything, so there are letters of advice from TV producers, acceptance notes for submissions and invoices from the BBC and Channel Four. Though his sit-com was ultimately rejected, the note from the producer at Channel Four suggested that Pete’s work was very good, witty and well-written, but needed more character development for it to be a full-blown TV series. Knowing my dad, he would have read that, and simply said ‘what do they know?’ and put the script back into his folder and moved onto something else. Pete was always writing or playing word games. He would stand at the bar, deep in thought and I would ask what was up, he would reply with something along the lines of ‘I can make 13 words from ‘Teachers Whiskey’’. He loved words, and plenty of his songs make use of this skill, that’s no lie, it Stroo! That particular song, ‘Stroo!’, makes me laugh, with Pete proving his spelling-bee credentials with the line ‘There’s no F-in shirts’. I may be biased but I believe that his writing skills are best showcased in two wonderful songs. Firstly, perhaps showing his skill for concise character development that Channel Four missed in his sit-com, is ‘Lower Side of Upper Middle Class’, written in October 1967 but still being requested by the audience in the 1980s. A tale of a rather uppity family thinking they are somewhat better than their social standing. The meandering verses are filled both with wit and satire and is well-worth listening to a few times. I feel blessed, I have access the other fifteen or so verses that Pete wrote for this song over the years and not one of the written versions matches the songs I’ve heard recorded! Pete often wrote topical verses to songs on his lunchbreaks at Bemmie’s, or on his way to a gig, stuck in traffic – the only record being a mental note of the lyrics and chords. The second song to showcase his skill is a true masterpiece. Little Ragamuffin tells the story of a young and emerging Bob Dylan, performing in Gerde’s Bar in Greenwich Village with a ‘beat up guitar’. There is a line that I wished I’d been able to ask my dad about. A verse discussing other notable acts and their demise, Phil Ochs, Paul Clayton and Woody Guthrie, and includes reference to ‘the only threat from England’ turning to telling dirty jokes. I’d like to know who he is referencing here; I like to think it’s himself; I am probably wrong. His song writing continued long after he stopped performing. Some of his later songs include ‘Revelations on Cosmetic Surgery’, ‘It’s Hard Being a Teenage Mum’, and ‘The Final Protest Song’ that refers to ECGs, Stannah stairlifts and LSD being replaced by HRT. He was a writer, and never stopped writing.

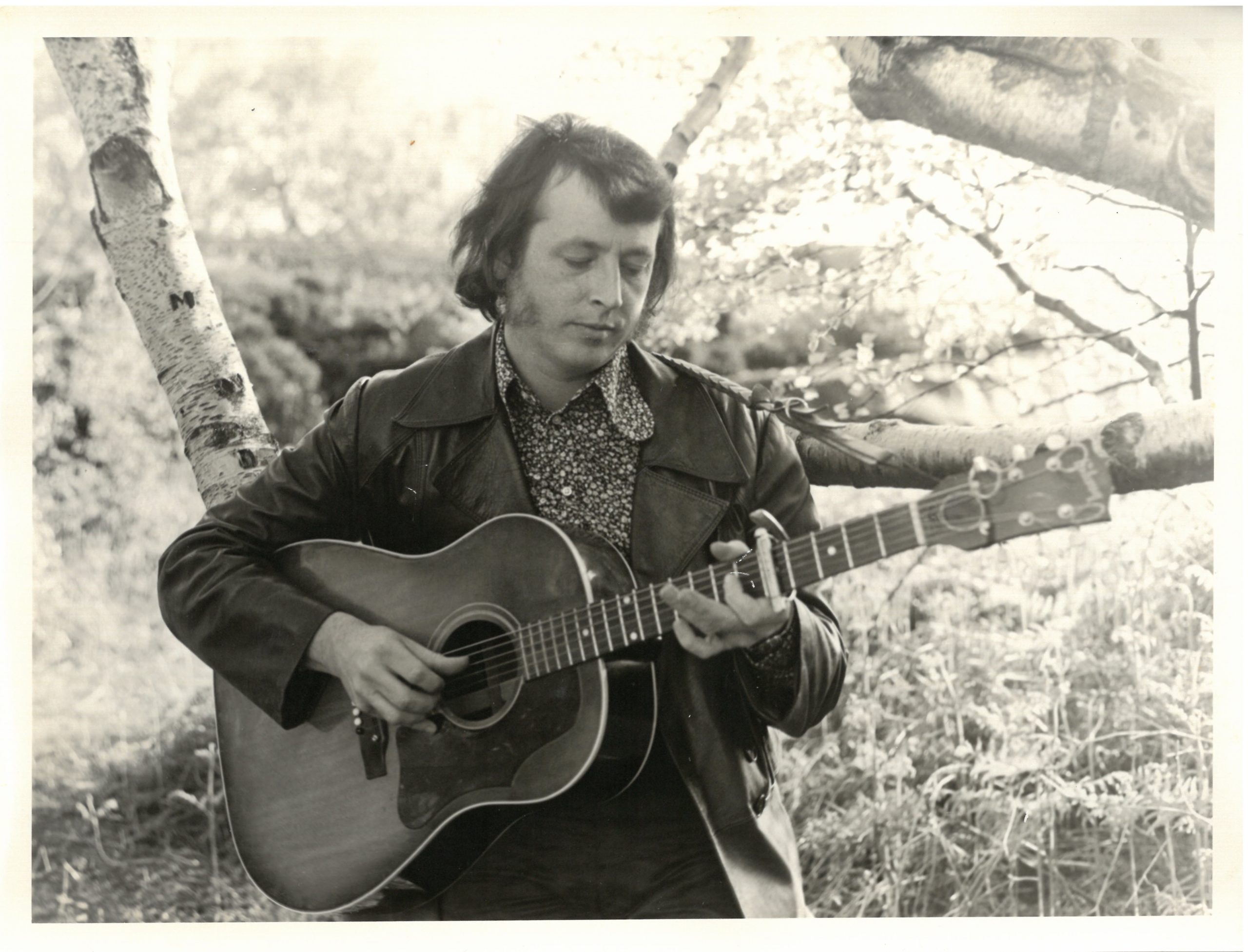

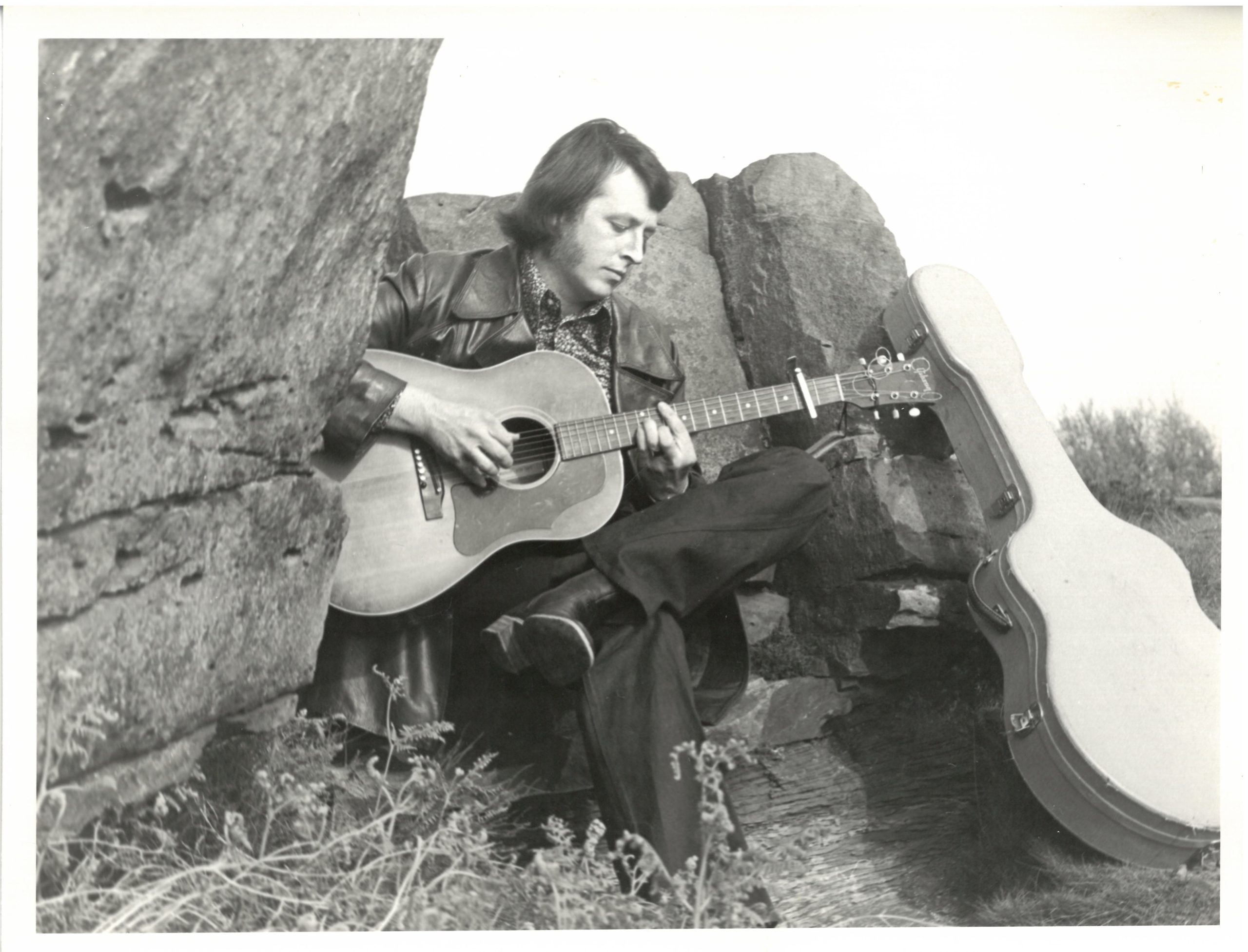

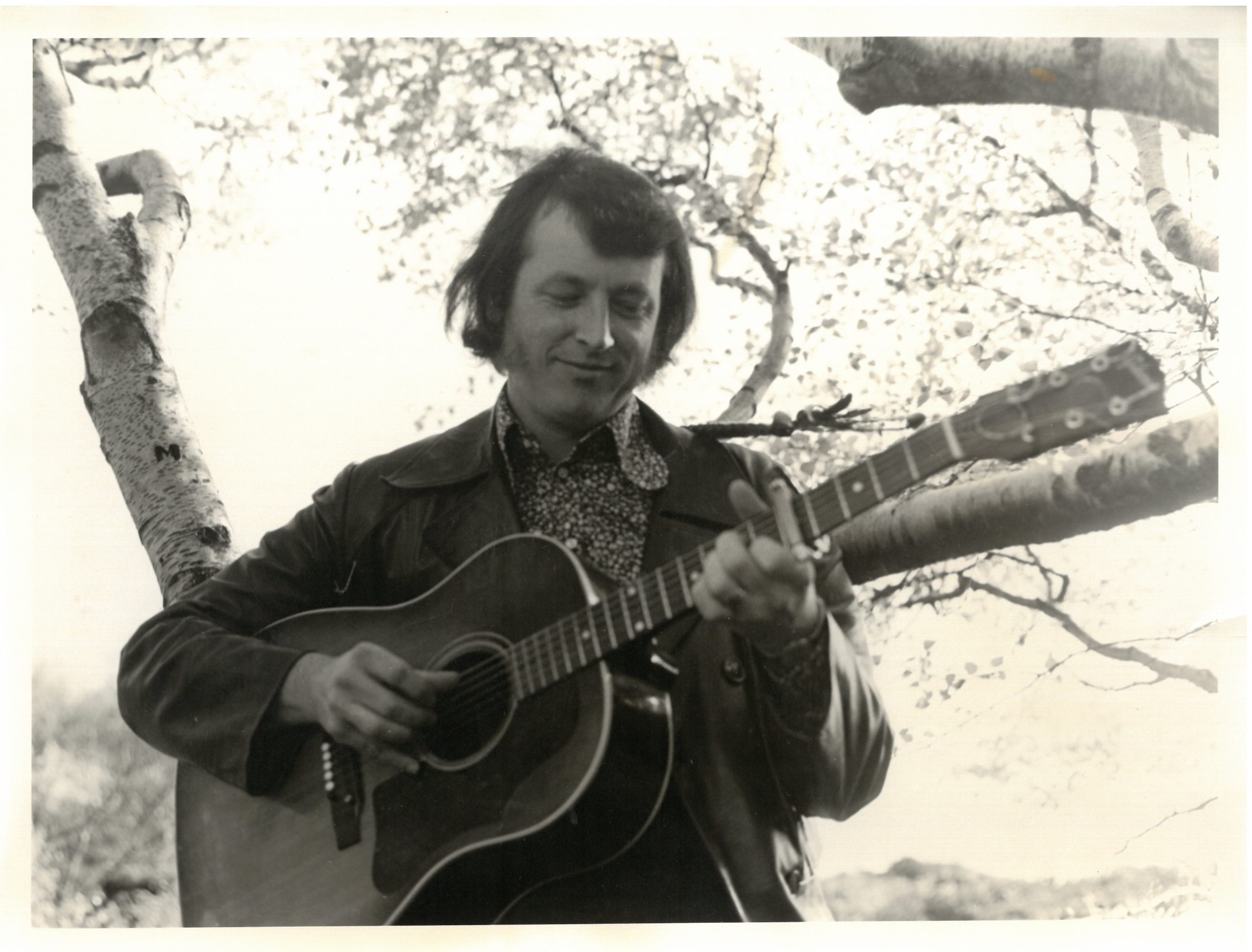

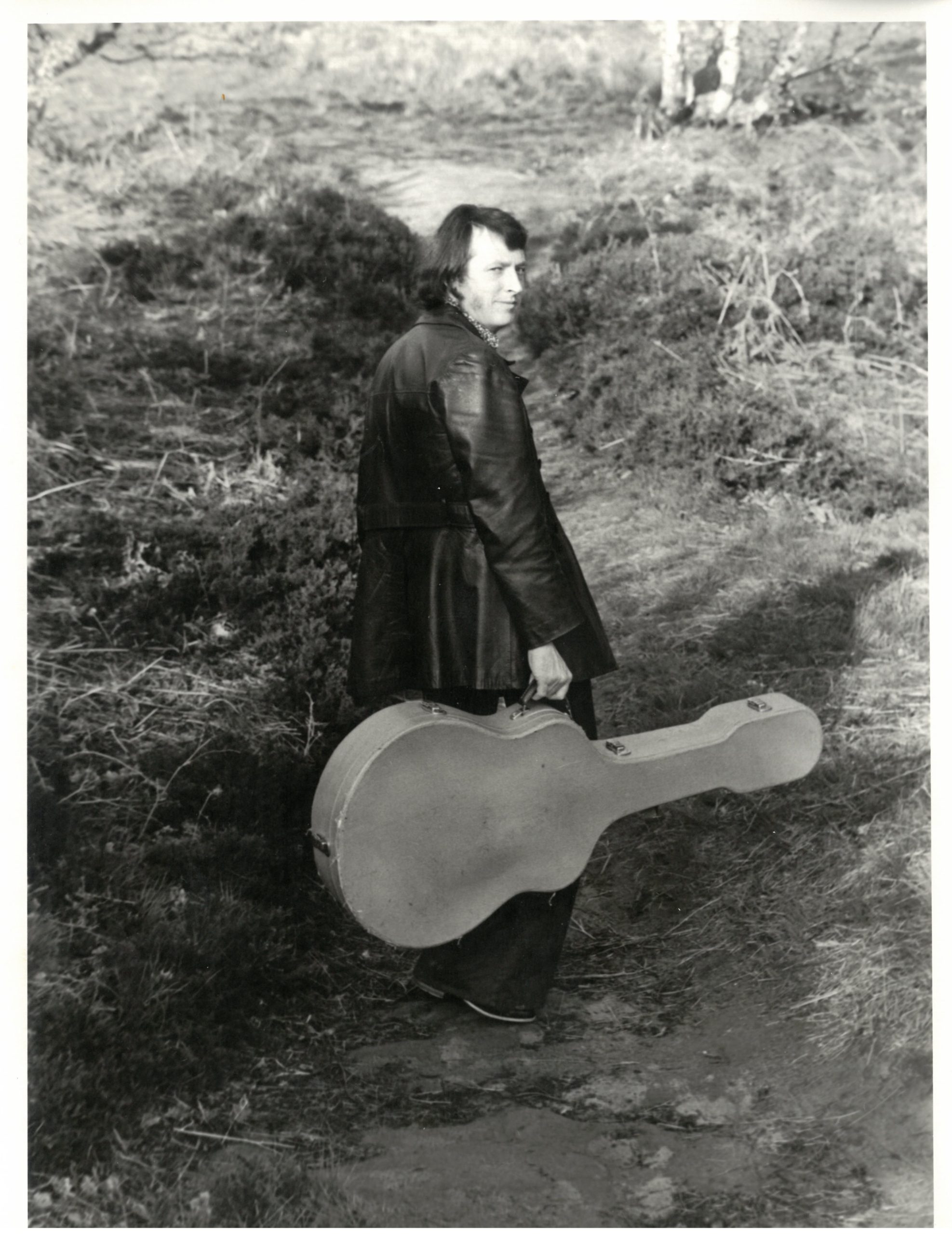

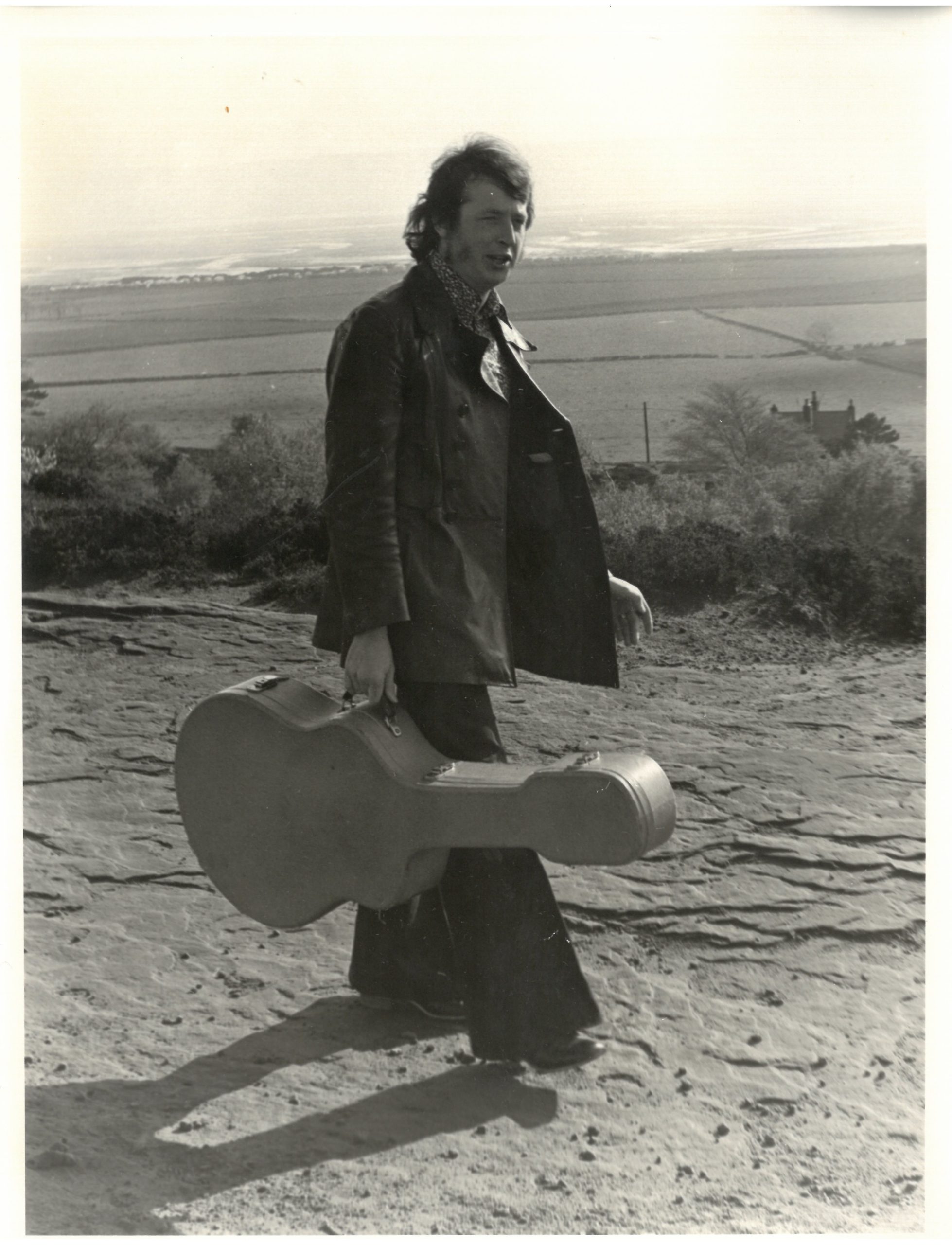

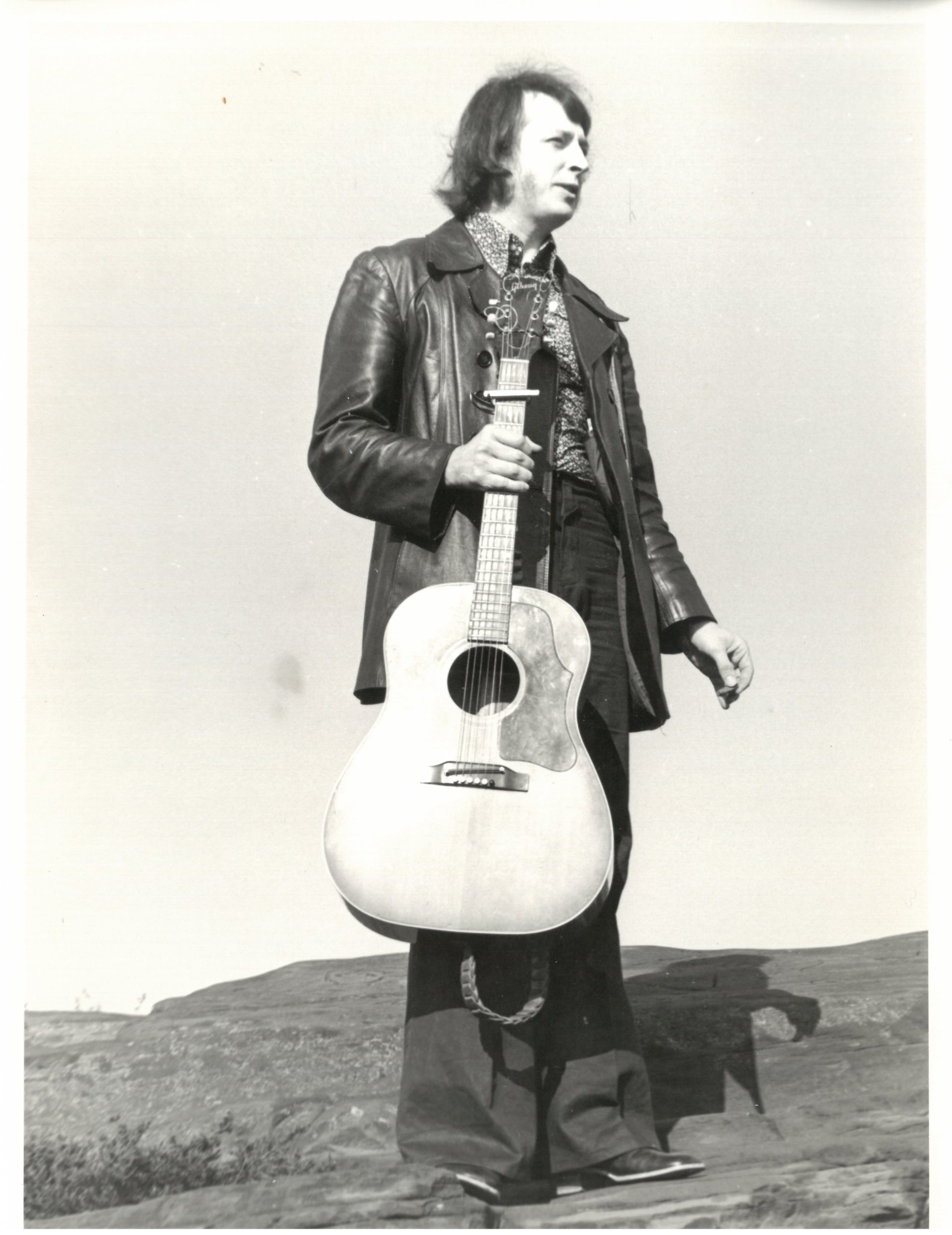

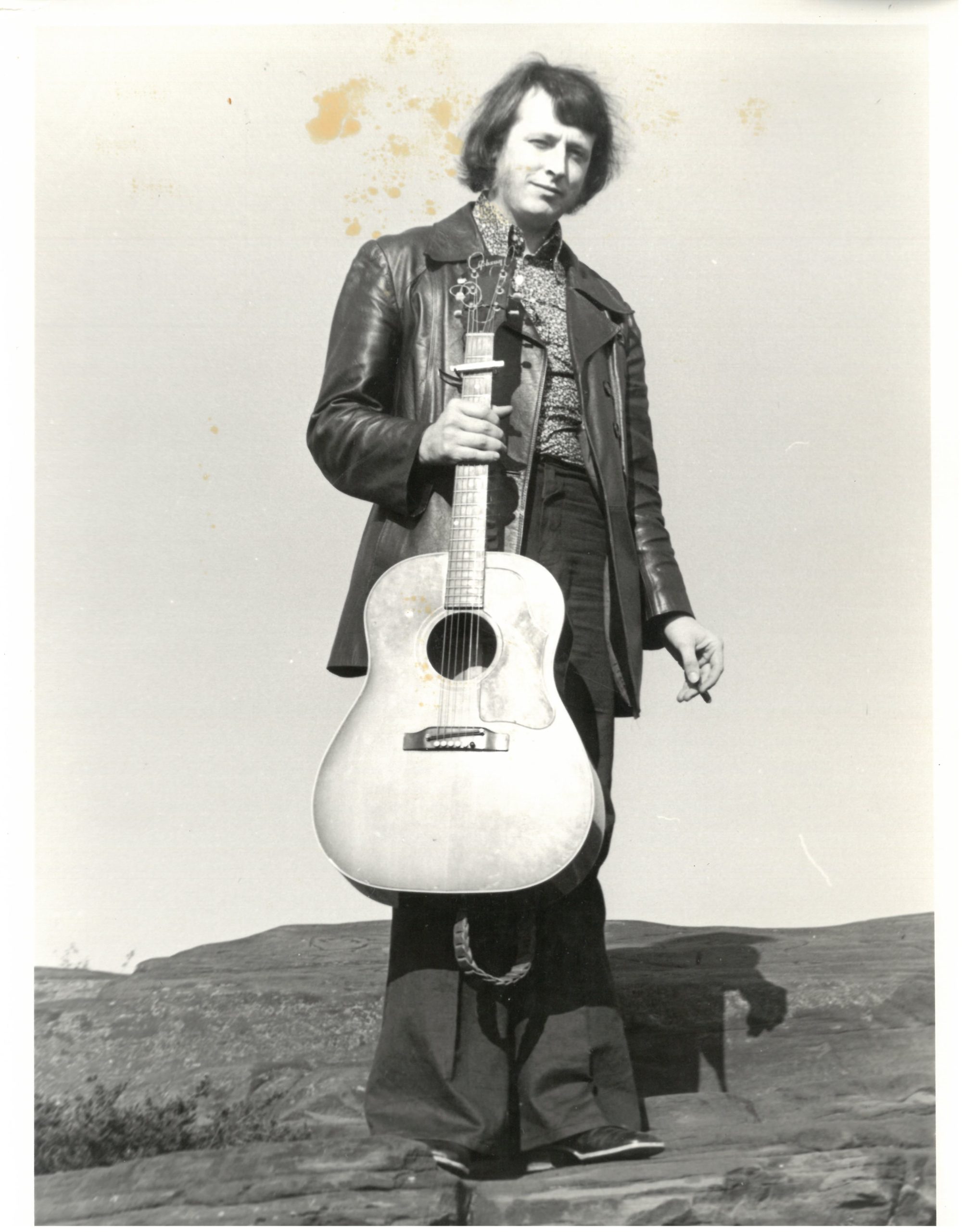

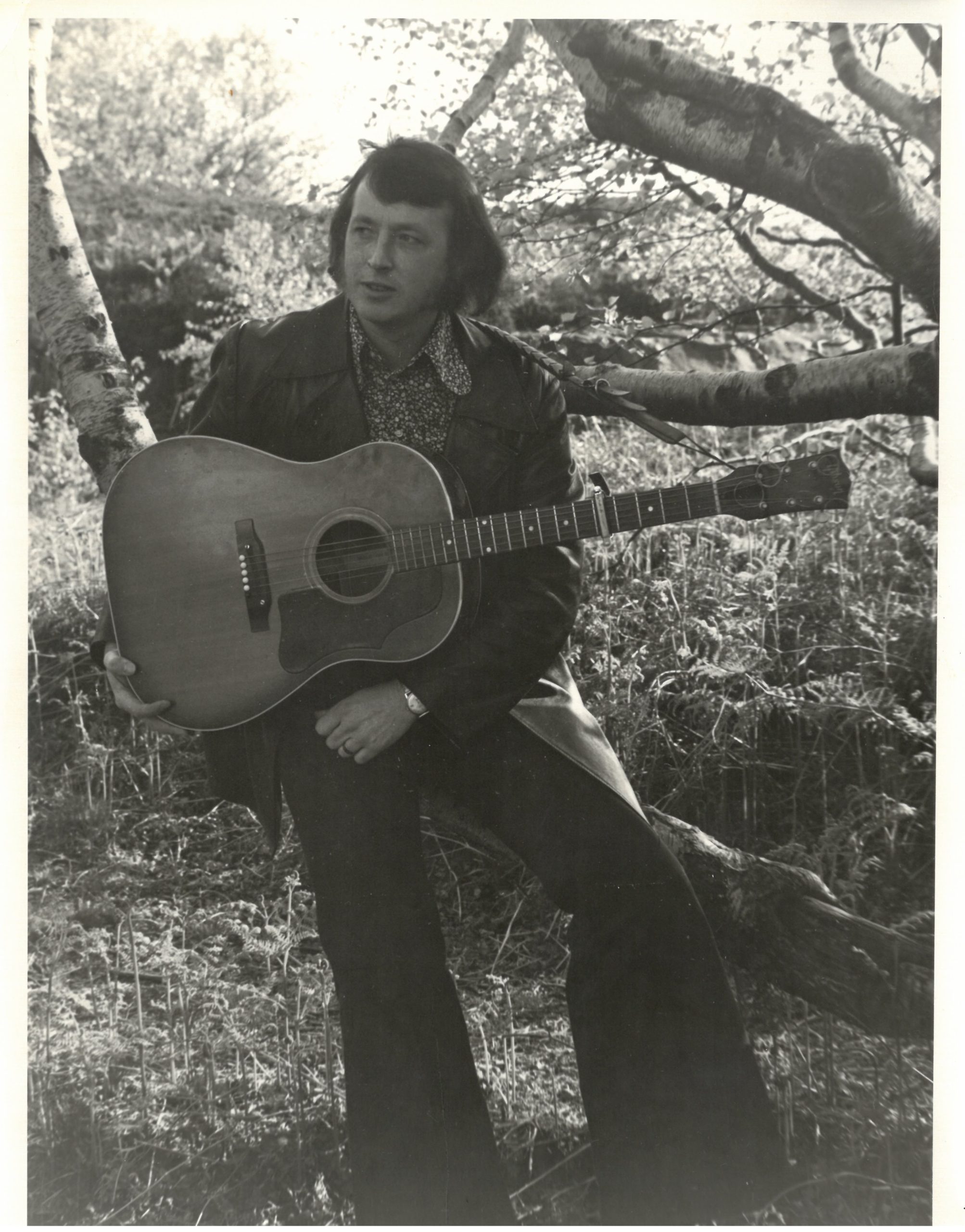

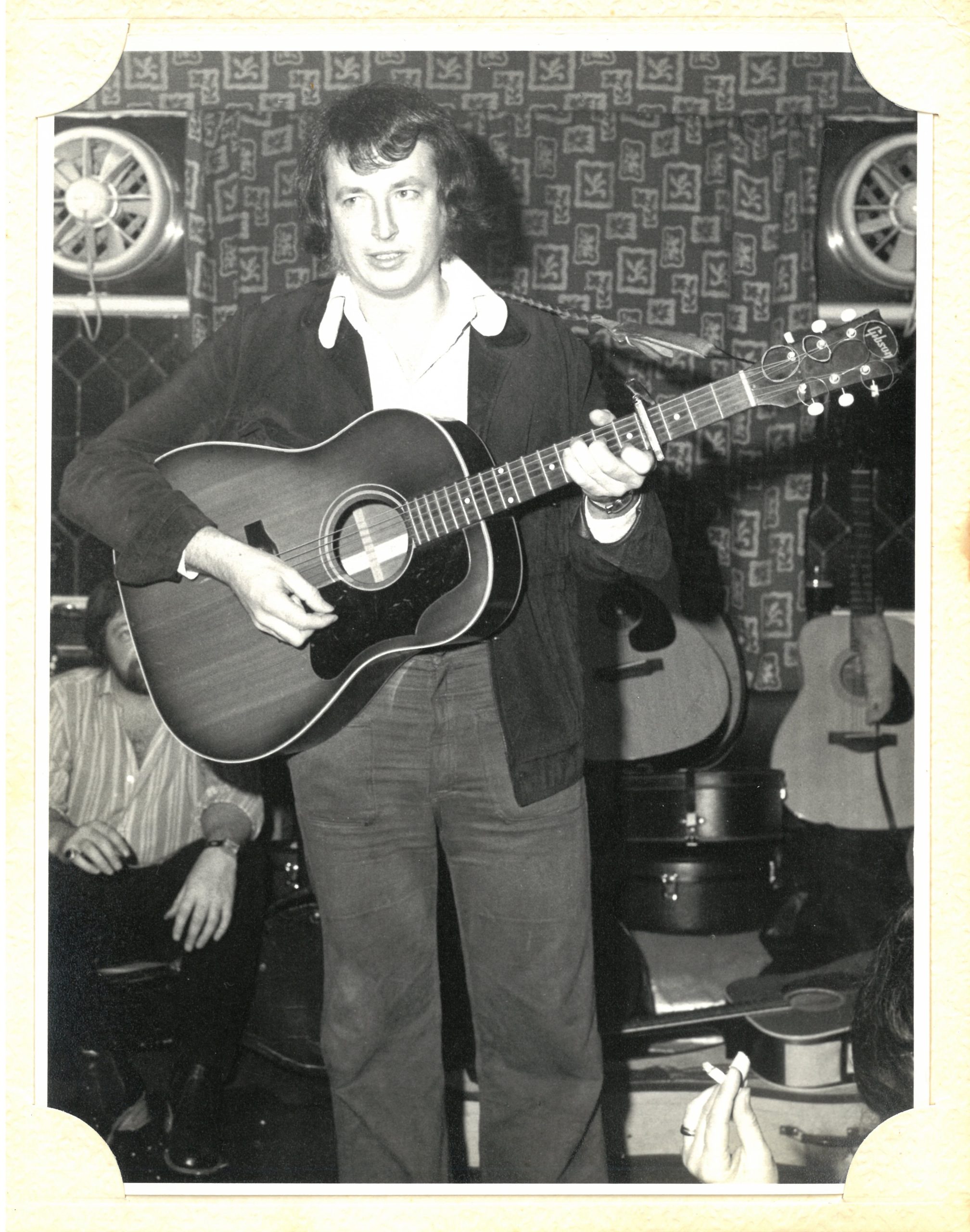

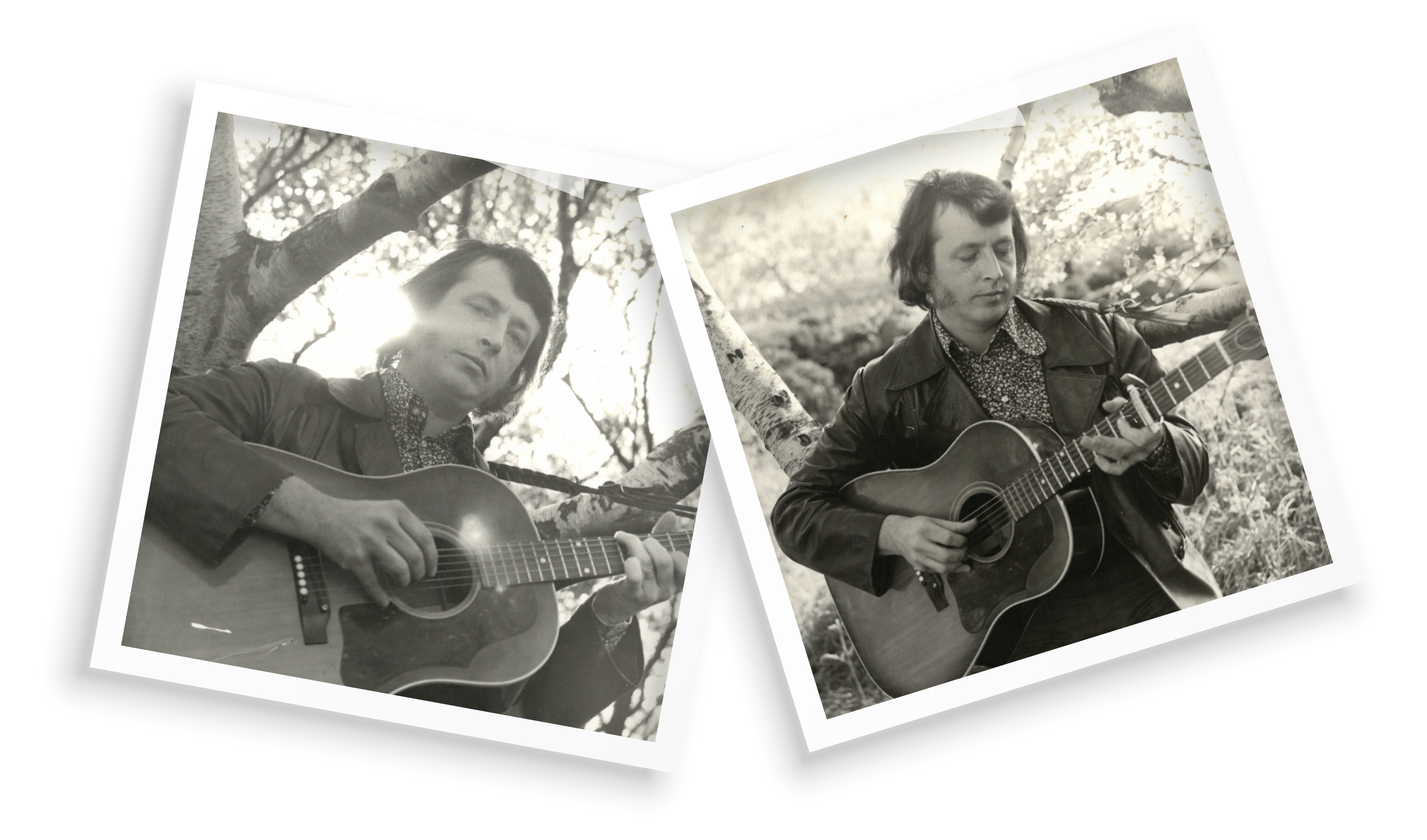

Performing was something that Pete loved, but he was equally happy with the trusty Gibson J-45 across his shoulders, playing at the top of the stairs or in the kitchen at the family home. I have fond memories of returning home from school to the sounds of the guitar, and occasionally harmonica, emanating from upstairs, or being in bed early, before my dad had gone to the pub for last orders, listening to the music he was playing. Though I found it fascinating, and in some way comforting, to hear it, I was never encouraged to pick up a guitar for myself. I think my dad believed if I was interested, I’d do it myself, like he had done back in the 1950s. He also did not want me to see or hear him perform, and only reluctantly gave me copies of his recordings after many begging requests. I was under strict instructions to only play them in the car, when I was driving alone. In some ways, despite the stage presence, the off-mike wanderings, witty and sharp one-liners and his skill at dealing with heckles, Pete was inherently shy and quite introverted.

It is clear that Pete was proud of his writing, and of his music, and fiercely protective of both. Writing this piece, and recording with Brian, has made me think that so much of it needs to be shared and preserved, and this has helped me to realise two things that I should do. Firstly, compile his type-written lyrics into an electronic format. This will be a long task, but I will undoubtedly discover some hidden gems I have not yet read. And secondly, write up and complete his novel, based on his time in a printing factory with characters based on people he worked with, and knew from the folk scene. Some of you may be in there, somewhere. Like his music, I was forbidden from reading his novel, ‘when I’m gone’ was his reply, for years and years. So now is the time. I have realised how lucky I was to be able to hear my dad play at home, and though I couldn’t understand the lyrics of his songs, or follow the music with any musical understanding, it was simply magical. I may not have been to one of my dad’s gigs, but I can, at least, listen to a few of them, and perhaps more importantly listen to people who did see him and try to Keep Folk Talking about Youngie, my dad. Enjoy the music, enjoy, or cringe, at the jokes and listen to the songs a few times – there’s so many hidden references you don’t get immediately.

LISTEN TO THE tribute

spoken by Richard Young

We’ve been fortunate enough to retrieve a recording of one of Pete Young’s short stories, as read on Radio Merseyside – ‘A Man Next Door,’ available to listen to today on Openhouse Studio.

READY FOR ANOTHERstory

READY FOR ANOTHERstory

Take a look in to all our artists for your next trip down memory lane…